Scrolls, Circling and Hostage Posters: My Visit to a Simchat Torah Service as a Muslim

As some of you read in an opinion article I wrote a few weeks ago for The Toronto Star, I had the unique opportunity and privilege to attend a Jewish High Holiday service at a conservative Toronto synagogue recently. I chose to attend the service as part of an assignment for a course I’m taking at Emmanuel College, University of Toronto right now, as part of my (probably overally ambitious!) pursuit of an M.A Theological Studies. A version of that assignment, the purpose of which was to recount and reflect on my experience attending a place of worship other than my own, is shared below.

(Pexel)

It was the colourful stained glass windows depicting Jewish objects, symbols and scenes from the Torah at the front and on both sides of the hall that first drew my attention. There was so much to look at within those pictures – and it surprised me to see Biblical imagery in a synagogue. I had always associated those images on stained glass windows exclusively with churches.

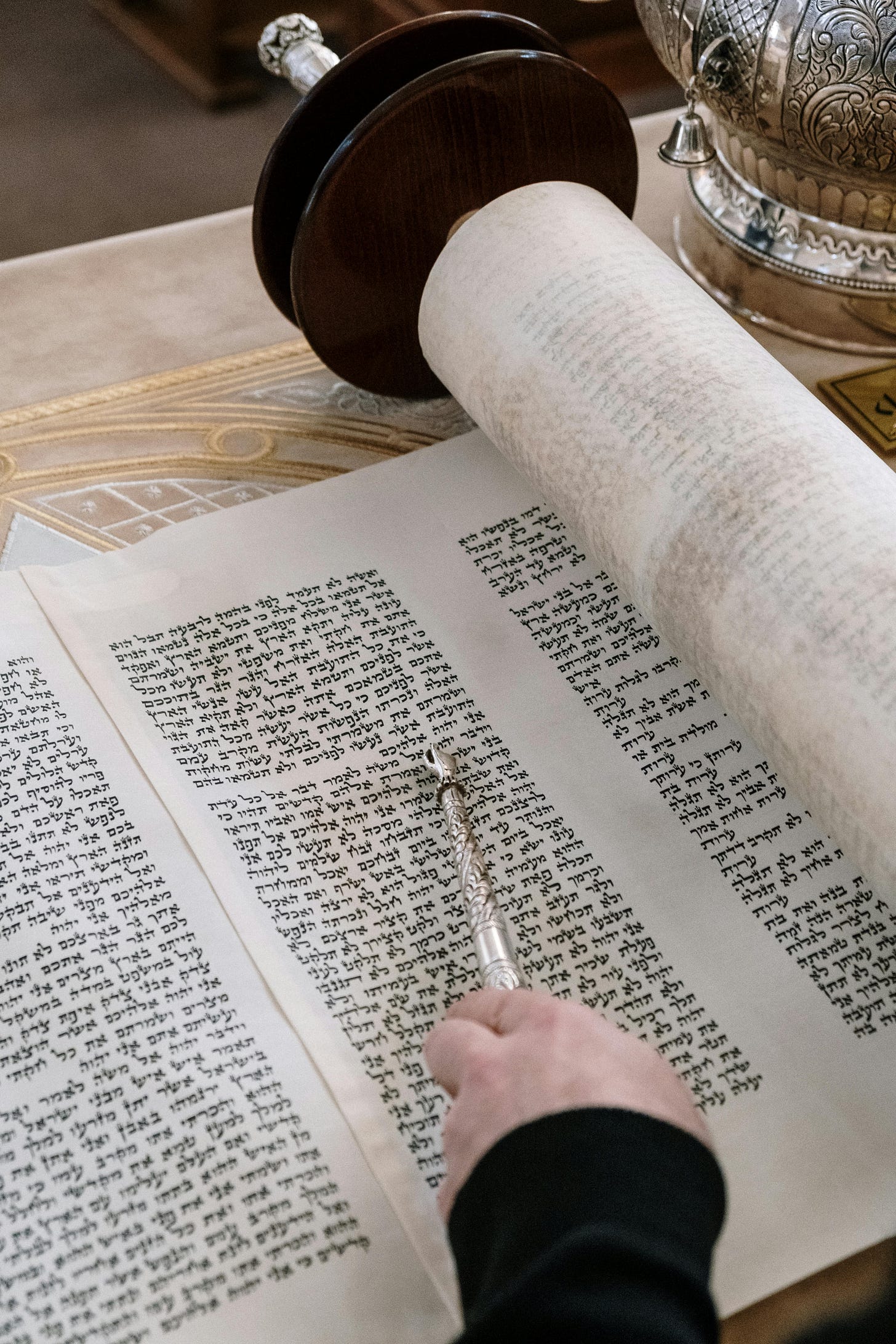

The second object that caught my eye was a large tall and rectangular-shaped structure situated at the back of the two-level stage, yet very much visible to the entire congregation. Engraved with beautiful designs (which the Rabbi told me afterwards was a Biblical visualization of wings) I realized that this object was functional only after several people sitting in the pews were called on to the stage to slide back what became clear were two doors that opened on either side to reveal several tall and regal-looking scrolls. This, I learned, was the Torah Ark, an ornamental chamber that nestles the Torah scriptures.

The third feature I noticed were the blown-up pictures of Israeli hostages hanging from the lower stage - a poignant reminder of the ongoing human suffering of Israeli Jews living in Israel.

At one point, Rabbi Jordan Bendat-Appell began calling for volunteers from the congregation to come to the stage. He then carefully removed each scroll from the Ark and handed it to the volunteer, all the while verses from the Torah were being sung by another rabbi on the lower stage. After a few minutes of the Torah being read directly from one of the scrolls, the members climbed down the steps from the stage and began encircling the room while holding the scrolls. As they came downstairs, the rabbi called for additional members to volunteer to carry the scroll and follow them around the room, again while singing. Several others moved forward to take part. This series of circuits of singing and dancing with the Torah, I learned, is called hakafot, and represents wholeness. “There’s a sense of becoming interconnected through circling,” Rabbi Jordan told me in a conversation afterwards. “We’re sort of wrapping the Torah into our lives and we're wrapping ourselves into the Torah.”

I also learned that The Torah was being read from three scrolls. The last portion of Deuteronomy was read from the first scroll, and the first portion of Genesis was read from the second. The third scroll was used to read the maftir, which is the passage that concludes the Torah reading.

During this ceremony, we were occasionally summoned by the rabbi to consult the books in front of us. They were sitting on a ledge that hung from the back of each pew, to follow along with his reading of the story of Moses' death and the story of Creation.

After the hakafot, the members who had been holding the scrolls gathered at the front and danced joyously. Rabbi Jordan then announced that the aliyah would begin. The aliyah (which has a double meaning: to immigrate to Israel but also to rise/ascend) gives everybody the opportunity to rise to the Torah, and is meant to be accessible to the masses, and not something that’s just read and absorbed by a religious elite. “We want everybody to feel connected to it, which is a really ancient Jewish value of education and bringing everybody into contact with our text and with our spiritual life,” he explained to me.

During the service, the Rabbi told the congregation that two ‘stations’ would be set up on both sides of the room at the very last row of pews. The stations consisted of a leader/rabbi unrolling and laying part of the scroll out on a table and allowing each member who had lined up in a cue beside him to recite a prayer of blessings. Not every member chose to do this, but my guess is that most congregants did. Afterwards, and during this process, other people gathered in small groups to chat, catching up with each other, asking about family, children, etc. This portion of the sermon, which took about 30-25 minutes, felt quite relaxed and informal - the atmosphere again was light and jovial.

Huppah

Eventually, Rabbi Jordan announced from the stage that we would begin the next portion of the ceremony, which would involve honouring two couples in the community for their commitment and community service. The first couple rose and walked to one corner of the room with their family members. In the corner, the family was given a blue and white shawl, called a huppah, to carry as a canopy. Each member of the family held one of the four poles and the couple being honoured walked beneath the canopy as they all retreated back into the main room, while verses from the Torah were being recited. They walked down the aisle in the middle of the pews. The rabbi recited a prayer, and the family returned back the same way to the corner in the same manner. This time, however, they did so amidst lots of cheers and cries of Mazal Tov! Mazal Tov! among the congregants. Rabbi Jordan then proceeded to honour the second woman and her family in the same way. This ceremony, I learned afterwards from Rabbi Jordan, is called Chatan (which means groom) Kallat (bride) Torah and is simply another way to honour the family for their service.

As a Muslim who attends mosque regularly, I found it quite eye-opening to visit a synagogue and observe a service as sacred as the Simchat Torah. I was curious to observe the similarities and differences. There were plenty of both to take in, but one of the starkest differences I took away was less theological. I found it quite interesting for instance to observe the size of the community, and the way it was described by its own congregants. It felt tiny in comparison to my own local mosque, which, on a quiet day, sees about 600 people enter its doors for a (regular weekly type of) program. On Islamic holidays, we typically have upwards of 7,000 people, even if they happen to fall on a weekday. This in comparison was a daytime program, and there was an evening celebration the night before which more people attended.

During the ceremony, I spoke at length with a former president of the center, and learned that it currently served 140 members and has been struggling with maintenance-related challenges over recent years. I asked him if he felt that this community has, like so many churches, experienced a trend towards lower attendance over the last decade (and longer) and if so, what he attributed it to. “Distractions,” he responded, adding that yoga classes, dance classes and other extracurricular activities were increasingly keeping families too busy to attend synagogue. An additional conversation I had a few days later with a former member of this congregation revealed that membership at this synagogue has been declining over recent years.

The former president also made an important distinction between attendance at conservative and orthodox synagogues: Because orthodox Jews are not permitted to drive on holy holidays, they tend to buy homes around synagogues. When house prices rise in these areas, the children are not able to afford living in the area any longer, and hence live farther away, making it more difficult to attend services.

‘Chaos’

The other difference I found quite striking from my experience attending my local mosque was how nearly every person I interacted with opened the conversation with a chuckle, saying: “This is not your ordinary service! It’s quite chaotic today!”

“So I’ve heard,” I would respond with a smile. My friend, who I had attended the service with, had mentioned this to me a few times beforehand, adding that it just might be the perfect day to visit the synagogue because it would be more lively. I understood this to mean that an ‘ordinary’ service just involved sitting and listening to the Rabbi address the congregation. And if that was the case, then, yes - with the varied aliyah and bride/groom ceremonies involved - the program was a bit more dynamic. But the choice of the word ‘chaotic’ was amusing to me. Chaos at the mosque meant children running around uninhibited, lots of women chatting loudly during the televised program, people trying not to step over each other as hot dishes are served by volunteers to members sitting on the ground at sufros (long mats rolled out onto the floor to eat at). So this orderly and small group of people making their way around the pews and lining up to recite from the Torah appeared pretty orderly from my vantage point!

During the quieter moments of the service, when the Torah was being recited by the rabbi’s at the front, I was left to mull over the words in the books in front of us, and take in my surroundings - mainly to the stained glass windows, wishing I had a deeper knowledge of stories from the Torah to be able to decipher them and their meaning.

Other times, I would turn my attention back to the front, where the faces of Israeli hostages - men, women, and babies - stared back at me.

When I made my decision to visit a synagogue for this assignment, I made an intentional choice to separate my own on-going rage and despair over the hundreds of thousands of innocent Palestinians that have - and are still - paying the price for the actions Hamas took that day. It was non-sensensical and unjust to associate the Israeli perpetrators of terrorism in Gaza and Lebanon right now with the people I would be sitting among. I still vividly remember all the hostile stares I received from fellow commuters on the London Underground back in 2003, after four bombers detonated themselves and 52 other people in central London in the professed name of Islam. The anti-Muslim sentiment in the UK where I lived at that time was higher than that it had ever been and I’d despised every minute of the association people would make between visible Muslims like myself and those crazed terrorists.

But the presence of these posters in the synagogue spurred me to think of something else. Since October 7 last year, community members at some Canadian mosques and Islamic centers have been discouraged from wearing or displaying symbols of Palestinian solidarity. The reasoning is that we risk upsetting our pro-Israeli neighbours and local political leaders, many of whom have taken an explicit and aggressively one-sided position on the Israel/Palestine conflict. Thinking about this as I gazed at the overt display of posters in front of me made my stomach churn. The difference in each community choosing to display these sentiments - or not - highlights an underlying inequity in Canada, where racialized groups feel pressured to self-censor due to a perceived or real threat to their safety, acceptance, or status in society. These Jewish community members appeared to feel more secure in openly supporting Israel within their place of worship, because the same level of scrutiny or potential backlash simply does not exist. It’s a vastly uneven playing field, and one that is certainly fuelling the pro-Palestinian movement and undoubtedly anti-Semitism as well.

Our common humanity

My visit to a synagogue was a needed reminder of the common humanity that unites us all, and it was comforting to have been received as warmly as I was. I was always surprised to hear many people say upon greeting me: “Thank you for honouring us with your presence!” because it was I who felt grateful for being permitted to attend at a politically sensitive time and being a visible Muslim.

The visit has unlocked a new set of questions for me about Judaism and reinforced my determination to learn more about the tradition, and about Christianity, ideally from an insider-out perspective (as much as that’s possible).

Note to readers: I also hope to continue exploring these topics through an upcoming interfaith event at my local mosque (and if you’re looking for further details, just reach out to me).

Thank you, Shenaz, for being openhearted and curious and for sharing this experience with us.

Thank you for sharing your experience. If you ever want to interview a Muslim that spent five years in a Catholic school let me know. It would be a great story!